Germans

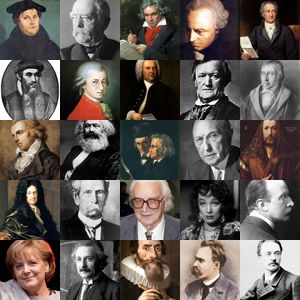

1st row: Martin Luther • Otto von Bismarck • Ludwig van Beethoven • Immanuel Kant • Johann Wolfgang von Goethe |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~160 000 000[1] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

German: High German (Upper German, Central German), Low German (see German dialects) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Roman Catholic, Protestant (chiefly Lutheran) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Austrians, Swiss Germans, other Germanic peoples, Sorbs, Lietuvininks, Prussian Latvians |

The Germans (German: Deutsche) are people descended from several Germanic tribes that inhabited what became the German-speaking part of Europe, which was collectively known as Germany.

With the founding of the modern nation-state of Germany, which occurred in 1871 and didn't include all of German-speaking Europe, the term Germans came to primarily mean residents of that country. Within modern Germany, Germans in this narrow sense have been defined by citizenship (Federal Germans, Bundesdeutsche), distinguished from people of German ancestry (Deutschstämmige). Historically, in the context of the German Empire (1871–1918) and later, German citizens (Imperial Germans, Reichsdeutsche) were distinguished from ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche).

Of approximately 100 million native speakers of German in the world, about 66–75 million consider themselves Germans. There are an additional 80 million people of German ancestry mainly in the United States, Brazil, Canada, Argentina, France, Russia, Chile, Poland, Australia and Romania who most likely are not native speakers of German.[39]

Thus, the total number of Germans worldwide lies between 66 and 160 million, depending on the criteria applied (native speakers, single-ancestry ethnic Germans, partial German ancestry, etc.). In the U.S., 43 million, or 15.2% of the population, identified as German American in the census of 2000.[40] Although the percentage has declined, it is still more than any other ethnic group.[41] According to the U.S. Census Bureau – 2006 American Community Survey, approximately 51 million citizens identify themselves as having German ancestry.[42]

Today, peoples from countries with a German-speaking majority or significant German-speaking population groups other than Germany, such as Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Luxembourg, have developed their own national consciousness and usually do not refer to themselves as Germans in a modern context.

Contents |

Ethnic Germans

The term Ethnic Germans may be used in several ways. It may serve to distinguish Germans from those who have citizenship in the German state but are not Germans; or it may indicate Germans living as minorities in other nations. In English usage, but less often in German, Ethnic Germans may be used for assimilated descendants of German emigrants.

Ethnic Germans form an important minority group in several countries in central and eastern Europe—(Poland, Hungary, Romania, Russia) as well as in Namibia (German Namibian), Brazil (German-Brazilian) (approx. 3% of the population),[43] Argentina (German-Argentine) (approx. 7,5% of the population)[44] and Chile (German-Chilean) (approx. 4% of the population).[45]

Some groups may be classified as Ethnic Germans despite no longer having German as their mother tongue or belonging to a distinct German culture. Until the 1990s, two million Ethnic Germans lived throughout the former Soviet Union, particularly in Russia and Kazakhstan.

In the United States 1990 census, 57 million people were fully or partly of German ancestry, forming the largest single ethnic group in the country. States with the highest percentage of Americans of German descent are in the northern Midwest (especially Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan) and the Mid-Atlantic state, Pennsylvania. But Germanic immigrant enclaves existed in many other states (e.g., the German Texans and the Denver, Colorado area) and to a lesser extent, the Pacific Northwest (i.e. Idaho, Montana, Oregon and Washington state).

Notable Ethnic German minorities also exist in other Anglosphere countries such as Canada (approx. 10% of the population) and Australia (approx. 4% of the population). As in the United States, most people of German descent in Canada and Australia have almost completely assimilated, culturally and linguistically, into the English-speaking mainstream.

History

The Germans are a Germanic people, which as an ethnicity emerged during the Middle Ages. From the multi-ethnic Holy Roman Empire, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) left a core territory that was to become Germany.

Origins

The area of modern-day Germany in the European Iron Age was divided into the (Celtic) La Tène horizon in Southern Germany and the (Germanic) Jastorf culture in Northern Germany. The predominant Y-chromosome haplogroup in Germans is R1b, followed by I and R1a; the predominant mitochondrial haplogroup is H, followed by U and T.[46]

The Germanic peoples during the Migrations Period came into contact with other peoples; in the case of the populations settling in the territory of modern Germany, they encountered Celts to the south, and Balts and Slavs towards the east.

The Limes Germanicus was breached in AD 260. Migrating Germanic tribes commingled with the local Gallo-Roman populations in what is now Swabia and Bavaria.

The migration-period peoples who would coalesce into a "German" ethnicity were the Saxons, Anglii, Franci, Thuringii, Alamanni and Bavarii. By the 800s, the territory of modern Germany had been united under the rule of Charlemagne. Much of what is now Eastern Germany remained Slavonic-speaking (Sorbs and Veleti).

Medieval history

A German ethnicity emerged in the course of the Middle Ages, under the influence of the unity of Eastern Francia (later Kingdom of Germany) from the 9th century. The process was gradual and lacked any clear definition.

After Christianization, the Roman Catholic Church and local rulers led German expansion and settlement in areas inhabited by Slavs and Balts (Ostsiedlung). Massive German settlement led to their assimilation of Baltic (Old Prussians) and Slavic (Wends) populations, who were exhausted by previous warfare.

At the same time, naval innovations led to a German domination of trade in the Baltic Sea and parts of Eastern Europe through the Hanseatic League. Along the trade routes, Hanseatic trade stations became centers of German culture. German town law (Stadtrecht) was promoted by the presence of large, relatively wealthy German populations and their influence on political power.

Thus people who would be considered "Germans", with a common culture, language, and worldview different from that of the surrounding rural peoples, colonized trading towns as far north of present-day Germany as Bergen (in Norway), Stockholm (in Sweden), and Vyborg (now in Russia). The Hanseatic League was not exclusively German in any ethnic sense: many towns who joined the league were outside the Holy Roman Empire and a number of them may only loosely be characterized as German. The Empire was not entirely German either.

Early Modern period

It was only in the late fifteenth century that the Holy Roman Empire came to be called the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. It was not exclusively German, and notably included a sizeable Slavic minority. The Thirty Years' War, a series of conflicts fought mainly in the territory of modern Germany, confirmed the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. The Napoleonic Wars gave it its coup de grâce.

Since the Peace of Westphalia, Germany had been "one nation split in many countries" (Kleinstaaterei). The Austrian–Prussian split, confirmed in 1871 when Austria remained outside of the Imperial Germany, was only the most prominent example.

In the nineteenth century, after the Napoleonic Wars and the fall of the Holy Roman Empire (of the German nation), Austria and Prussia emerged as two competitors. Austria, trying to remain the dominant power in Central Europe, led the way in the terms of the Congress of Vienna. The Congress of Vienna was essentially conservative, assuring that little would change in Europe and preventing Germany from uniting.

.jpg)

The terms of the Congress of Vienna came to a sudden halt following the Revolutions of 1848 and the Crimean War in 1856. This paved the way for German unification in the 1860s.

In 1870, after France attacked Prussia, Prussia and its new allies in Southern Germany (among them Bavaria) were victorious in the Franco-Prussian War. It created the German Empire as a German nation-state, effectively excluding the multi-ethnic Austrian Habsburg monarchy and Liechtenstein. Integrating the German speaking Austrians nevertheless remained a desire for many Germans and Austrians, especially among the liberals, the social democrats and also the Catholics who were a minority in Germany.

During the 19th century in the German territories, rapid population growth due to lower death rates, combined with poverty, spurred millions of Germans to emigrate, chiefly to the United States. Today, roughly 17% of the United States' population (23% of the white population) is of mainly German ancestry.[47]

Twentieth century

The dissolution of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire after World War I led to a strong desire of the population of the new Republic of German Austria to be integrated into Germany or Switzerland.[48] This was, however, prevented by the Treaty of Versailles.

The Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler, attempted to unite all Germans (Volksdeutsche) into one realm, including ethnic Germans in eastern Europe, many of whom had emigrated more than one hundred fifty years before and developed separate cultures in their new lands. This idea was initially welcomed by many ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia, Austria, Poland, Danzig and western Lithuania. The Swiss resisted the idea. They had viewed themselves as a distinctly separate nation since the Peace of Westphalia of 1648.

After World War II, because of the ostensible reasons for war and in retaliation for Nazi excesses, eastern European nations, including areas annexed by the Soviet Union and Poland, expelled ethnic Germans from their territories, including Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Yugoslavia. Most of the 12 million ethnic German refugees fled to western Germany and Europe, the United States, and South America.[49]

After WWII, Austrians increasingly saw themselves as a nation distinct from other German-speaking areas of Europe. Recent polls show that no more than 6% of the German-speaking Austrians consider themselves as "Germans".[50] Austrian identity was emphasized along with the "first-victim of Nazism" theory.[51] Today over 90 percent of the Austrians see themselves as an independent nation.[52]

1945 to present

Between 1950 and 1987, about 1.4 million ethnic Germans and their dependants, mostly from Poland and Romania, arrived in Germany under special provisions of (right of return). With the collapse of the Iron Curtain since 1987, 3 million "Aussiedler"—ethnic Germans, mainly from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union—took advantage of Germany's liberal law of return to leave the harsh conditions of Eastern Europe.[53] Approximately 2 million, just from the territories of the former Soviet Union, have resettled in Germany since the late 1980s.[54] On the other hand, significant numbers of ethnic Germans have moved from Germany to other European countries, especially Switzerland, the Netherlands, Britain, and Spain.

Subgroups

The Germans are divided into sub-nationalities, some of which form dialectal unities with groups outside Germany that are not considered "Germans". The Bavarians and Swabians maintain pronounced cultural identities. In the case of the Swabians, there was even a limited movement for Alemannic separatism. The Low German Platt speakers also retain a certain ethnic identity, while the Central German majority has largely abandoned individual nationalisms, though there is a strong cultural identity among the Rhinelanders. The most notable diversity among Germans is the culture of sailing and fishing in Northern Germany, while the rest of Germany has a culture of farming and castle romanticism, especially in Bavaria.

- High German

- Upper German

- the Bavarians (ca. 10 million) form the Austro-Bavarian linguistic group, together with those Austrians who speak German and do not live in Vorarlberg and the western Tyrol district of Reutte.

- the Swabians (ca. 10 million) form the Alemannic group, together with the Alemannic Swiss, Liechtensteiners, Alsatians and Vorarlbergians.

- High Franconian, is a transitional dialect between Upper German and Central German

- Central German dialect group (ca. 45 million)

- Central Franconian, forms a dialectal unity with Luxembourgish

- Rhine Franconian (Ripuarian, Kölsch)

- Thuringian

- Hessian

- Upper Saxon

- High Prussian

- German Silesian

- Upper German

- Low German (ca. 3–10 million), forms a dialectal unity with Dutch Low Saxon

- Low Saxon

- East Low German

- Yiddish dialects of Ashkenazi Jews in Germany and eastern Europe

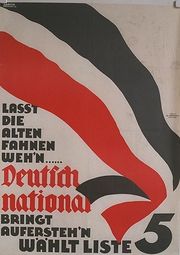

Nationalism

As in other European countries, nationalism came to Germany during the 18th and especially 19th century. German nationalism is traditionally based on language and culture, due to the lack of a centralized state. The aim of German nationalism in the 19th century was to unify the various smaller states into a German nation-state.

French suppression and Napoleonic wars are considered a main cause of nationalism in the German states. While the early national democratic movement, ca. 1830, had a strong internationalist face ("Young Germany" as a part of "Young Europe"), during the March Revolution of 1848/1849 the problem of ethnically mixed territories in central Europe became an important issue. Nonetheless, the (never realized) German liberal constitution of 1849 granted a free cultural development also to the "non German speaking parts of the people".

In the 19th century, German nationalism was closely associated with liberalism (see national liberalism) and calls for democracy. It was opposed by the rulers of the many monarchies in today's Germany and by reactionary forces. After the Vienna Congress, Prince Metternich was a staunch opponent of German nationalism, liberal values and calls for democracy. Black-red-gold, the colors of the modern German flag, that goes back to the 1848 revolutions and the calls for Germany unity, are traditionally seen as representing liberal, nationalist and republican values, as opposed to the Emperor's Black-white-red, that are traditionally seen as representing conservatism and monarchist values.

In 1871, a German nation-state was eventually founded, but without Austria.

German nationalism was later alloyed at the end of the nineteenth century with the high standing and worldwide influence of German science and culture, to some degree enhanced by Bismarck's military successes (1864–1871). During the following years a substantial part of Germans assumed a cultural and ethnic supremacy, particularly compared to their neighbors, the Slavs. But even in imperial Germany, nationalist forces were opposed by large internationalist movements, e.g. social democracy with more than 1 million members. Nationalists despised not only social democrats as Reichsfeinde (enemies of the Reich), but also Catholics, left liberals and Jews. -->

Nationalism increased during World War I. After the war and the disappointing peace terms, internationalism and moderate liberalism became unpopular in Germany and other countries. Realistic politicians, who tried to make Germany great again through conciliation with the Western powers, such as Gustav Stresemann, encountered strong opposition from conservative and ultranationalist forces on the political right. Among these a new sort of nationalism emerged, one that emphasized on biologicist concepts of nation; it culminated in Adolf Hitler's national socialism.

Possessing a German flag (and displaying it) is relatively uncommon in Germany, although that changed to a certain degree during the 2006 soccer world cup. The documentary film Deutschland. Ein Sommermärchen, which follows the German team from boot camp through the 2006 World Cup, shows the optimism by Germans during the journey.

The German flag is hated by some persons, who view themselves as belonging to the political left. Youssef Bassal, is a immigrant to Germany and also the owner of Berlin's biggest Germany flag. He said that leftists had criticized him for displaying that flag and that it has been stolen by hooded persons dressed in black once and once was burned.[55] During the 2010 soccer world cup leftist groups destroyed German flags. Many immigrants displayed German flags in order to show their commitment to Germany and several told the press that leftists tried had tried to destroy or destroyed theirs.[56]

Politicians (of the right and the moderate left) emphasize the need to distinguish between patriotism as the love of own's country and nationalism as hate against other countries, according to former President Johannes Rau.[57]

As a tree the Quercus robur (or "German Oak" as it is called in Germany) symbolizes Germany. "German Oak" is also a popular name for inns, sport clubs, ships and so on. In German culture the oak is believed to be a symbol of steadfastness and perservance. A common German saying is "The German oak does not mind" (Was stört's die deutsche Eiche"). The oak in German culture also is a symbol for peace. "Friedenseiche" (="oak of peace") is also the name of many inns, sportclubs and the like.

Religion

Today, Germans include both Protestants and Catholics, with each group about equally represented in Germany. Historically, Protestants formed the majority in the northern two-thirds of the country. With the loss of traditionally Protestant regions after World War II and many Protestants' turning to agnosticism and atheism, especially in the former East Germany, the two groups are about equally represented. Today, non-Christians constitute a majority in certain regions of Germany, both in urban as well as in rural (eastern) regions.[58] Other large groups of immigrants were or are mostly Catholics (e.g., Poles, Italians and Croatians).

The Protestant Reformation started in the German cultural sphere, when in 1517, Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses to the door of the Schlosskirche ("castle church") in Wittenberg. Among Protestant denominations, the Lutherans are well represented among Germans, while Calvinists are historically to be found primarily near the Dutch border and in a few cities like Worms and Speyer.

The late nineteenth century saw a strong movement among the Jews in Germany and Austria to assimilate and define themselves as Germans, i.e., as Jewish Germans (a similar movement occurred in Hungary). In conservative circles, their acculturation was not always embraced. Beginning with social tensions in the 1920s, the rise of Nazis in the 1930s meant an increase in anti-Semitism, as they used the Jewish population as scapegoats for national problems. The Nazis conceived and carried out extreme discrimination and an effort to exterminate the Jews, leading to the deaths or exile of almost all of the pre-World War II Jewish population.

Today Germany is trying to better integrate Gastarbeiter (guest workers) and more recent refugees from the former Yugoslavia, such as Bosnian Muslims.

Minorities

Since the post-World War II decades and especially the later 20th century, the German-speaking countries of Europe have reflected striking demographic changes resulting from decades of immigration. These changes have led to renewed debates (especially in the Federal Republic of Germany) about who should be considered German. Non-ethnic Germans now make up more than 8% of the German population. They are mostly the descendants of "guest workers" who arrived in the 1960s and 1970s. The Poles, Turks, Moroccans, Italians, Greeks, Portuguese, Spanish, and people from the Balkans form the largest groups of non-ethnic Germans in the country.

As of December 2004, about seven million foreign citizens were registered in Germany, and 19% of the country's residents were of foreign or partially foreign descent (including persons descendent or partially descendent from or who are ethnic German repatriates). The young are more likely to be of foreign descent than the old. Thirty percent of Germans aged 15 years and younger have at least one parent born outside the country. Certain cities in particular have attracted large populations of foreign born people. In the city of Nuremberg 67 percent of all children were of foreign or partially foreign descent (including persons descending or partially descending from ethnic German repatriates), in Frankfurt am Main that was 65 percent and in Düsseldorf and Stuttgart 64 percent.[59] 96 percent of the persons who have at least one parent born abroad lived in Western Germany or Berlin.[60] The largest group (2.7 million) are descended from ethnic Turks.[61]

A significant number of German citizens (close to 5%), although traditionally considered ethnic Germans, are in fact foreign-born. They retain cultural identities and languages from their native countries. This sets them apart from native Germans. Foreign-born repatriates are not unique to Germany. The English and British equivalent legal term of lex sanguinis (law of blood) stipulates that citizenship is inherited by the child from his/her parents. It has nothing to do with ethnicity.

Ethnic German repatriates from the former Soviet Union constitute by far the largest such group and the second largest ethno-national minority group in Germany. The repatriation provisions made for ethnic Germans in Eastern Europe are unique and have a historical basis. These were areas where Germans traditionally lived, that is, where they had migrated and maintained some German language and culture. Nonetheless, the fact of their separation meant they developed differently from populations within German borders.

The Volga Germans, descendants of ethnic Germans who settled in Russia during the eighteenth century, have presented a controversial case of "repatriation". They have been permitted to claim German citizenship even though neither they nor their ancestors for several generations had been to Germany. In contrast, persons of German descent living in North America, South America, Africa, etc. do not have an automatic right of return. They must prove their eligibility for German citizenship according to applicable German nationality law. Other countries with post-Soviet Union repatriation programs include Greece, Israel and South Korea.

Unlike these ethnic German repatriates, some non-German ethnic minorities in the country, including some who were born and raised in the Federal Republic, choose to remain non-citizens. Although recently German citizenship laws have been relaxed to allow such individuals to become naturalized citizens, many choose not to give up allegiance to the countries of their ethnic roots. They live in Germany under the status of an alien resident. Although this status means that people lack certain political rights, they often can still get work and free public higher education, and travel freely abroad.

As a result, close to 10 million people permanently living in the Federal Republic today distinctly differ from the majority of the population in a variety of ways such as race, ethnicity, religion, language and culture. Official statistical sources often fail to account for them as minorities because such sources traditionally survey only German citizens classified under the so-called jus sanguinis (right of blood) system, limiting citizenship to those with German forebears, which has been in effect in Germany since the nineteenth century. It has only recently been partially replaced by the alternative jus soli (right of soil) system, allowing citizenship to all individuals born there. This situation contributes to the invisibility of Germany's minorities.

See also

- List of Germans

- Culture of German-speaking Europe

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Genetic history of Europe

- Ethnic Germans, also referred to as the German diaspora

- German eastward expansion

- German idealism

- German Jews

- German American

- German Canadian

- German Mexican

- German Brazilian

- Names for the German language

- Immigration to Germany

- List of Alsatians and Lorrainians

- List of Austrians

- List of Swiss people

- List of terms used for Germans

- Organised persecution of ethnic Germans

References

- ↑ Germans and foreigners with an immigrant background. 156 is the estimate which counts all people claiming ethnic German ancestry in the U.S., Brazil, Argentina, and elsewhere.

- ↑ 66.42 million is the number of Germans without immigrant background, 75 million is the number of German citizens Germans and foreigners with an immigrant background

- ↑ Deutsche Welle: 2005 German Census figures

- ↑ CIA World Factbook - Germany: People

- ↑ 49.2 million German Americans as of 2005 according to the "US demographic census". http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/IPTable?_bm=y&-reg=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201:535;ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201PR:535;ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201T:535;ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201TPR:535&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201PR&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201T&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201TPR&-ds_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_&-TABLE_NAMEX=&-ci_type=A&-redoLog=false&-charIterations=047&-geo_id=01000US&-format=&-_lang=en. Retrieved 2007-08-02.; see also Languages in the United States#German.

- ↑ A Imigração Alemã no Brasil | Brasil | Deutsche Welle | 25.07.2004

- ↑ 2001 Canadian Census gives 2,742,765 total respondents stating their ethnic origin as partly German, with 705,600 stating "single-ancestry", see List of Canadians by ethnicity.

- ↑ «Relaciones culturales entre Alemania y la Argentina» The Embassy claims there are 600,000 people of German descent and 50,000 German citizens. Buenos Aires: Embajada de Alemania en Argentina. Consulted April 4, 2009.

- ↑ According to the Centro Argentino Cultural Wolgadeutsche] there are 2,000,000 descendants of Volga Germans in Argentina

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Argentine

- ↑ France

- ↑ Alsatians

- ↑ a result of population transfer in the Soviet Union; see ethnologue

- ↑ The Australian Bureau of StatisticsPDF (424 KB) reports 742,212 people of German ancestry in the 2001 Census. German is spoken by ca. 135,000 [1], about 105,000 of them Germany-born, see Demographics of Australia

- ↑ German Embassy in Chile.

- ↑ http://demo.istat.it/str2006/query.php?lingua=ita&Rip=S0&paese=A11&submit=Tavola

- ↑ South Tyrol in figures. Provincial Statistics Institute.

- ↑ see page five, as of 2006

- ↑ German born only; United Kingdom: Stock of foreign-born population by country of birth, 2001

- ↑ INE(2006)

- ↑ 163 923 resident aliens (nationals or citizens) in 2004 (2.2% of total population), compared to 112 348 as of 2000. 2005 report of the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics. 4.6 million including Alemannic Swiss: CIA World Fact Book, identifies the 65% (4.9 million) Swiss German speakers as "ethnic Germans".

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ 2002 ce nsus; mainly in Opole Voivodeship, see German minority in Poland.

- ↑ census 2001

- ↑ Statistik Austria 2008

- ↑ Germans in South Africa

- ↑ Professor JA Heese in his book Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner (The Origins of Afrikaners) claims the modern Afrikaners (who total around 3.5 million) have 34.4% German heritage. How 'Pure' was the Average Afrikaner?

- ↑ EU Passport Gets Popular in Israel | Europe | Deutsche Welle | 21.07.2004

- ↑ German minority

- ↑ There are 6,000 Germans living in Uruguay today and 40,000 descendants of Germans

- ↑ Ethnic German Minorities in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia

- ↑ Land reform worries Bolivia's Mennonites

- ↑ (Dutch) "Bevolking per nationaliteit, geslacht, leeftijdsgroepen op 1/1/2008". Statistics Belgium. http://statbel.fgov.be/nl/modules/publications/statistiques/bevolking/Bevolking_nat_geslacht_leeftijdsgroepen.jsp. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ↑ Norway

- ↑ Ethnic groups around the world

- ↑ Amid Namibia's White Opulence, Majority Rule Isn't So Scary Now

- ↑ Dominican Republic

- ↑ in the German-Danish border region; see Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger

- ↑ (Spanish) Hablantes del alemán en el mundo

- ↑ [3] "Nearly 43 million people in the United States identify German as their primary ancestry, the U.S. Census Bureau reported in July 2004"

- ↑ This figure accounts for self-reported ancestry, rather than race or ethnicity. See demographics of the United States and European American for more information.

- ↑ [4] "Ancestry—German = 50,764,352"

- ↑ A Imigração Alemã| Brasil | Deutsche Welle | 14.01.2010

- ↑ German-Argentine Descendants of Germans in Argentina

- ↑ German in Chile.

- ↑ World Haplogroups Maps

- ↑ "US Census Factfinder". http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-_lang=en&-_caller=geoselect&-format=.

- ↑ Als Vorarlberg Schweizer Kanton werden wollte - Vorarlberg - Aktuelle Nachrichten - Vorarlberg Online

- ↑ refugee -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ [5]. Development of the Austrian identity .

- ↑ Peter Utgaard, Remembering and Forgetting Nazism, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2003), 188–189. Frederick C. Engelmann, "The Austro-German Relationship: One Language, One and One-Half Histories, Two States", Unequal Partners, ed. Harald von Riekhoff and Hanspeter Neuhold (San Francisco: Westview Press, 1993), 53–54.

- ↑ [6]

- ↑ "Fewer Ethnic Germans Immigrating to Ancestral Homeland"

- ↑ "External causes of death in a cohort of Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union, 1990-2002"

- ↑ Jörg Lau. Nachtwache an der Sonnenallee. July 1th 2010, Die Zeit. http://www.zeit.de/2010/27/Tuerken-Linke-Berlin?page=1

- ↑ Christoph Stollowsky. Verkehrte Welt: Autonome zerstören Deutschland-Fahnen türkischer Berliner. June 28, 2010

- ↑ Berliner Zeitung: Rau: Für ein Deutschland ohne Angst, last seen on January 24th, 2010.

- ↑ Daten des Statistischen BundesamtesPDF

- ↑ http://www.tagesschau.de/inland/meldung34348.html

- ↑ http://www.tagesschau.de/inla/meldung34348.html

- ↑ "Poll: Most Turks in Germany Feel Unwelcome", Deutsche Welle, March 13, 2008